Sustainability and the Role of Marketing in a Capitalist System

I’m in a graduate certificate program on Corporate Sustainability and Innovation. For a class on systems thinking, I wrote this paper, and am posting it here because I thought the information to be worth sharing. It’s not as comprehensive as I would like it to have been, but I had less than two weeks to work on it (while working the day job).

Capitalism is the primary economic system in use by the industrialized parts of the world. It has been responsible for bringing millions of people out of poverty, but it has also proven to be a broken system—one that has never been equitable or sustainable (Gilbert, 2019). A systems analysis can help understand the driving forces’ interrelationships and the embedded points of fragility affecting the sustainability of production and consumption in the United States’ capitalist economic system. Particular attention is given to the discipline and role of marketing, as it holds a unique position of leverage and responsibility, among the major system elements, for reforming the system towards sustainability. Sustainability is defined by the United Nations Brundtland Commission (1987) as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (p. 41). A comprehensive systems solution for the sustainability of capitalism would broaden the scope of analysis to include extensive governmental policy, but this analysis’ consideration of regulatory factors is kept to a minimum in order to focus on Industry and market activity.

A Brief History of Capitalism

To properly address the sustainability problems created by capitalism, it is critical to gain context by understanding the history and central themes of the system. Capitalism is based on private ownership and a market-based, free exchange of goods and services (Gilpin, 2018). This system, in its simplest forms of commodity production and exchange, can be traced back through much of human history, but eighteenth-century Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith, now known as “The Father of Economics”, is credited with having identified the principles that clarify the complexity of market transactions and laying the foundations for free market economic theory. In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Smith developed concepts including division of labor and how rational self-interest and competition can lead to economic prosperity (Greenspan & Wooldridge, 2018, p. 6). The word “capitalism”, however, didn’t emerge until the mid-1800s (Braudel, 1979), with the emergence of mass production and industrial labor forces.

Although there is variety in how individual countries’ capitalist economic systems manifest in relationship with their political and values systems, the overall intention of a capitalist system can be generalized. Capital, in this sense, refers to property in the form of money and physical assets. Capitalism, as a system, is meant to generate economic wealth, implicitly in order to improve a society’s quality of life and eliminate poverty and scarcity. However, given its fluid history, capitalism has no formally agreed-upon goal (Tantram, 2014).

The Role of Marketing in a Capitalist Economy

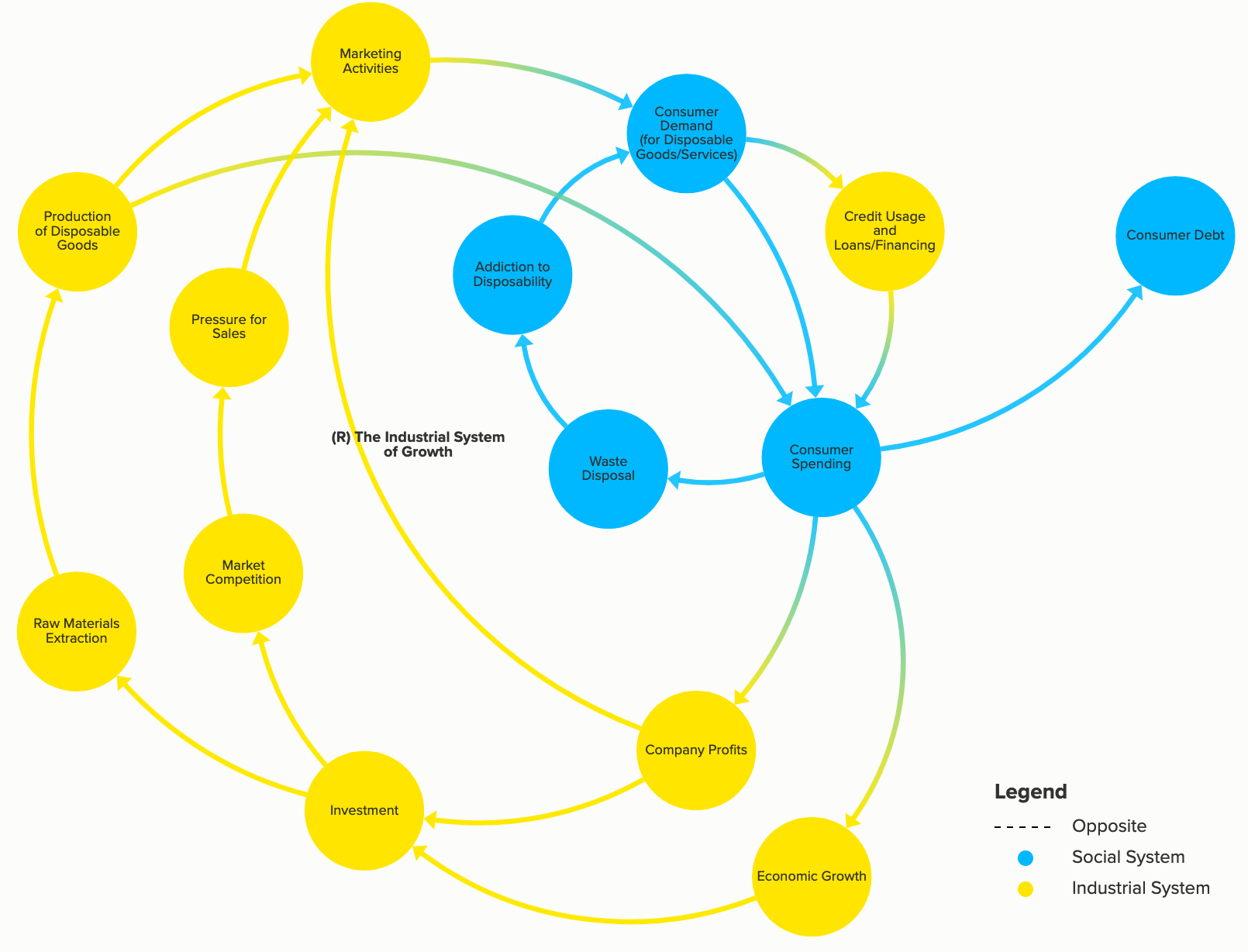

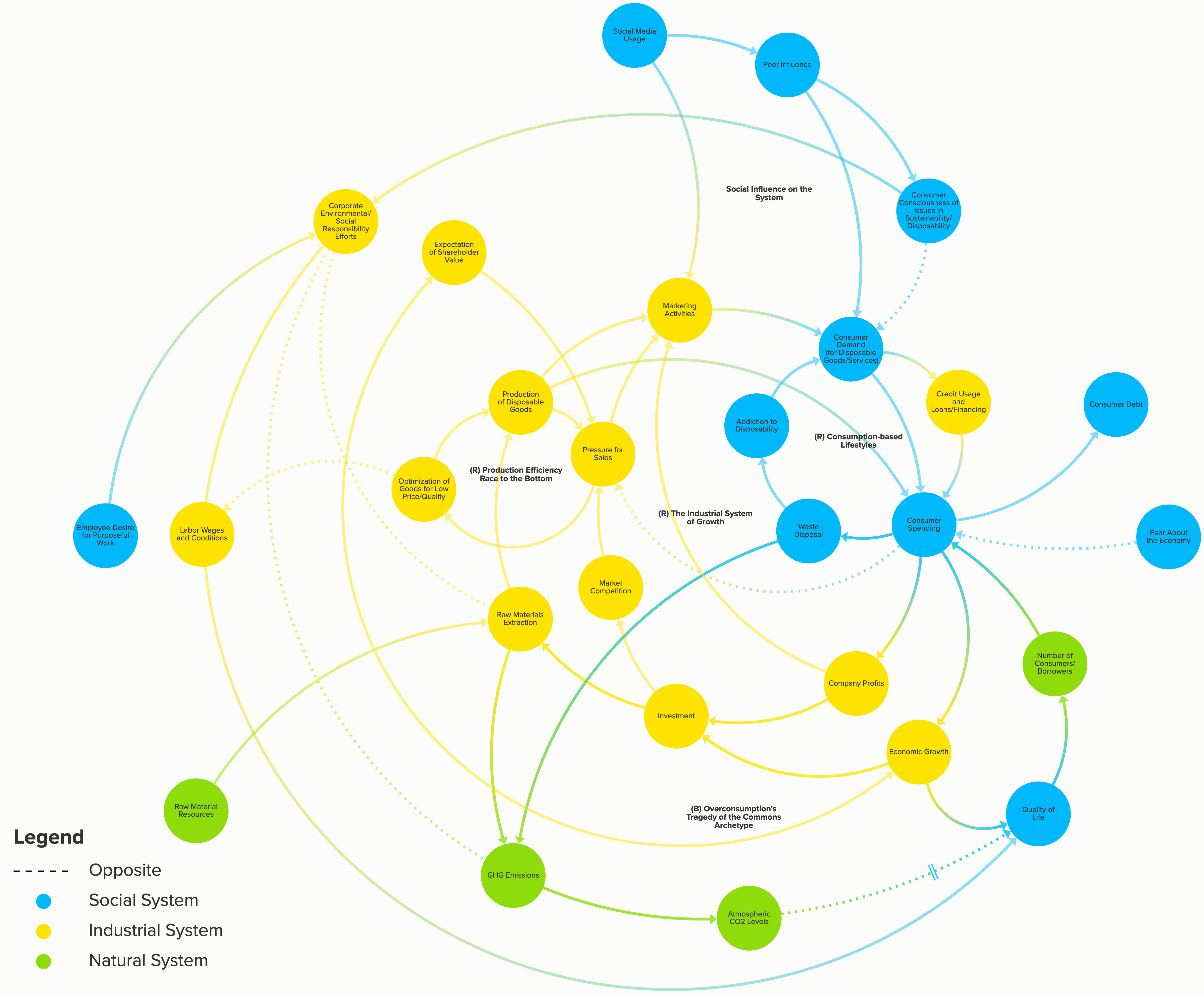

During the twentieth century, alongside the expansion of mass production and market-driven economics, the formal discipline of marketing emerged as a force that would both shape and change the world (Belz & Peattie, 2012, p. 6–7). Philip Kotler, known as “the father of modern marketing” says marketing’s job is “to create real value for some defined group”; that marketing is the enabler and the engine of capitalism; and that without it, capitalism would collapse (2016). A marketer creates this value for the system shown in Figure 1, through a broad range of brand-building and growth responsibilities, but specifics include pricing the product right, making it accessible to purchase, and promoting it in a way that the intended market becomes aware of it and desires it (Kotler, 2016). Early marketing efforts sought generally to create markets and demand for all the new mass-produced products. For especially expensive goods and services like homes, cars, educations, and vacations, marketers helped develop social acceptance of debt through credit cards, mortgages, and other forms of lending (Kotler, 2016). As the marketing discipline matured, its philosophy focused on the idea that business should be organized around meeting the needs and desires of consumers (Belz & Peattie, 2012, p.14).

Figure 1: The Industrial System of Growth

Figure 1: The Industrial System of Growth

The Problem with Capitalism

Former US Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich, has said, “There’s nothing inherently moral or amoral about any economic system. It depends on how it’s organized” (Kornbluth & Gilman, 2017). “Capitalism is the best economic system for producing the greatest volume and diversity of goods and services” (Kotler, 2016) and has generated the greatest accumulation of wealth in all of human history (Gilpin 2018). Perhaps it could eliminate poverty and scarcity altogether, but it has not yet done so—in fact the current system of capitalism in the United States has reached a point of reckoning. What was supposedly intended to benefit all of society is now only benefitting those with wealth, delivering extreme prosperity to the powerful minority of executives and shareholders while the percentage of financial gains going toward increasing labor wages has dropped dramatically (Kornbluth & Gilman, 2017). It’s become a reinforcing “Success to the Successful” system archetype.

Understanding how these unintended consequences came to be requires a retrospective. Americans have always tended to value the idea of free-market capitalism, even though what we have isn’t actually entirely market-based. Government sets regulations and enforces rules, such as those governing monopolies and contracts, as part of its system goal of maintaining social and economic stability. The rules of Industry, however, don’t establish a purpose. This lack of defined purpose has caused fragility in American capitalism (Tantram, 2014). For example, in the 1960s, as mass marketing was hitting its stride, the US government started regulating against things like advertising sugary foods to children—intended as a balancing factor to prevent Industry from adversely affecting human health. Corporations, in their bounded rationality, got upset, perceiving their “free-market” economic system as being under attack, and began using their economic leverage to pursue the political power necessary to ensure their needs as businesses were met by the legislative process. Over time, industry lobbyists managed to change the rules to favor corporate interests over social interests (Kornbluth & Gilman, 2017).

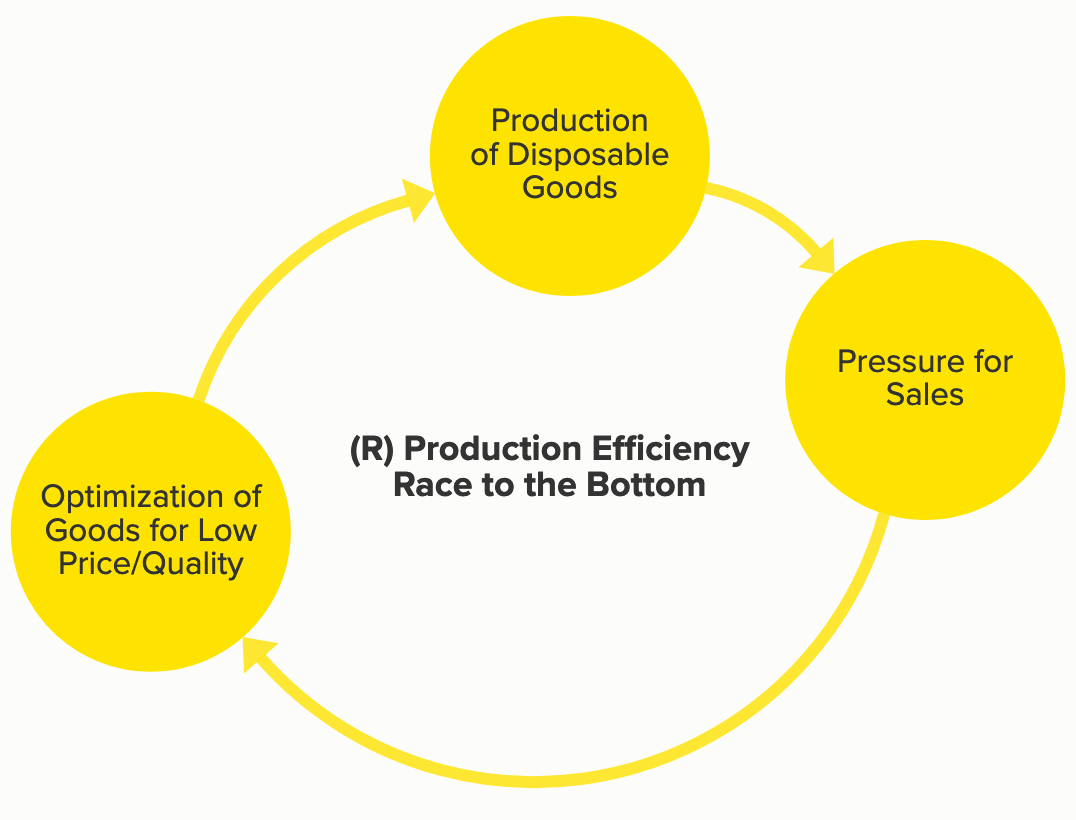

Meanwhile, the severity of the Great Depression had revealed another point of fragility in consumer capitalism—that when people have no money, or fear that they soon won’t, they don’t buy new things. They save what money they do have, and they use and repair products they already own. This is the worst thing to happen to a system that requires constant consumption of new things and growth at any cost; flows are cut off and the system fails. Depressions demonstrate that growth is not only unsustainable; it’s unstable in its own right (Jackson, 2010). But instead of addressing the root problem, Industry doubled down, with the short-term strategies of planned obsolescence and disposability—designing products to have a finite lifespan either through their functionality or aesthetics and fashion trends. Planned obsolescence and disposability represent a perpetual reinforcing loop of extraction, production, consumption, and investment of the kind that, as shown in Figure 2, further reduces costs and wages, and creates incremental product changes that satisfy our human obsession with novelty and disposability, all while appearing to signify a healthy economy (Formafantasma, 2019).

Figure 2: Reinforcing loop for lowering prices and quality in generating more sales

Figure 2: Reinforcing loop for lowering prices and quality in generating more sales

In reality, though, it is a race to the bottom. This “Fixes that Fail” system archetype continues to this day, and has recently worsened further, environmentally, due to products—particularly electronic ones—designed and engineered without any consideration for (or, in many cases, to prevent) post-use upgrade, repair, or recycling processes, complicating material recovery (Formafantasma, 2019). Our constant manufacturing of expendable non-necessities for the purpose of continued consumption-based profits, market expansion, and shallow novelty-based fulfillment comes with increasing and disastrous rates of environmental destruction and exploitation that will eventually cause system collapse and failure by means of climate change and resource depletion. We are reaching a limit to this kind of growth.

The Misdirected Power of Marketing

Donella Meadows, in her book Thinking in Systems, observes, “People within systems don’t often recognize what whole-system goal they are serving. ‘To make profits,’ most corporations would say, but that’s just a rule, a necessary condition to stay in the game. What is the point of the game?” (2008, p.161). Marketing’s goal, in the current consumer capitalist growth economy, is to sell materialism and consumption. As economist Tim Jackson quips, “People are persuaded to spend money we don’t have, on things we don’t need, to create impressions that won’t last, on people we don’t care about” (2010). This statement understandably could drive one to perceive marketers as evil or manipulative, but, on the contrary, the actual characteristics of marketers, generally, include a genuine desire to help people and create value and meaning for their customers by means of their win-win problem-solving mindset. Marketers have a healthy and creative competitive drive directed at improving customer relationships, and they’re energized by the promise of innovative approaches and new technologies to achieve those goals at scale (MacFarland, 2014). They mean so well, but their innovations serve a broken system.

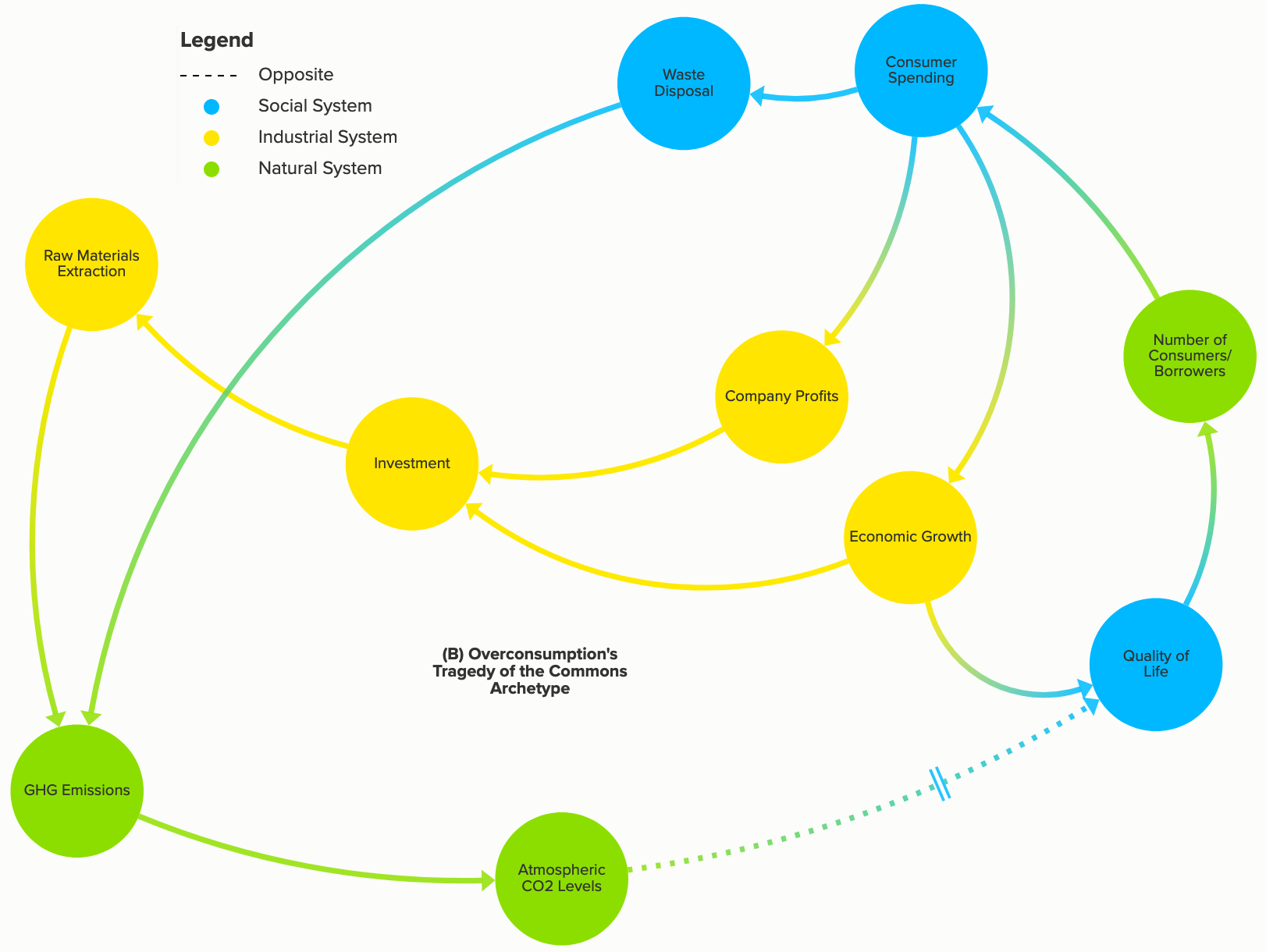

In a complex, broken system, no one is to blame. Replacing people in a system doesn’t fix the system. As long as the underlying structure and influences remain the same, the system behavior also remains the same. As such, all the energy marketers spend keeping up with the tactical knowledge of constantly changing marketing technology keeps them operating within existing system instead of questioning it. This is what the system, calibrated toward consumption, wants; the system is more efficient when its actors do not try to understand or question why they do what they are doing. It is easier to participate in destructive systems, as individuals and as businesses, when the negative consequences manifest far away and out of sight” (Formafantasma, 2019). It has not traditionally been a part of the marketer’s job to understand or be concerned with the social and environmental impacts of their products, packaging, etc., nor are these negative externalities a part of their cost and pricing structures. Rather, the effects of Industry greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, and labor abuses become the burden of the people they harm and the governments that work to remedy the harms, in a “Tragedy of the Commons” system archetype, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Overconsumption’s Tragedy of the Commons archetype

Figure 3: Overconsumption’s Tragedy of the Commons archetype

When people do realize their place in the larger, unsustainable system, among complex interrelationships of reinforcing structures, the feelings of powerlessness and entrapment can be incredibly disheartening. Marketing, as a discipline, faces a serious dilemma. Instead of “creating artificial demand for products and services by … encouraging increased consumption in order to maximize profits, [marketing] must be now perceived in the wider social context” (Rudawska, 2017). However, the personal and business risk associated with any one actor’s voluntary reduction in production- and consumption-related activity is enormous in the context of a system that isn’t changing—it would likely sabotage their job or business.

Except, of course, when it doesn’t. Marketing has always known its unique power to influence audiences, striving to create truly memorable, impactful impressions. The brave marketer can go against the flow, and, if the stars align, change the paradigm, and in effect position their brand as leader. The strategic marketer will recognize that being early to market with sustainable product and service solutions can be a lasting competitive differentiator. Marketers, uniquely situated at the nexus of business strategy, production, and consumption, are capable of playing a key role in redirecting capitalism’s trajectory toward sustainability.

Leverage Points

The most powerful leverage for changing a broken system is a paradigm shift. Donella Meadows says, “You could say that paradigms are harder to change than anything else about a system…. But there’s nothing physical or expensive or even slow in the process of paradigm change. In a single individual it can happen in a millisecond. All it takes is a click in the mind, … a new way of seeing” (2008, p.164). Meadows acknowledges, however, that paradigm shifts in whole societies take much longer, and when we talk about capitalism and consumption patterns, we’re talking about a societal level paradigm. But she suggests that the way to change a societal paradigm is through change agents in places of public visibility, power, and influence (2008, p.164). This is less about literal changes to the underlying structures, and more about establishing public awareness of the systemic problem, gaining and confirming public acceptance of structural change, and creating a movement favoring a more ideal goal.

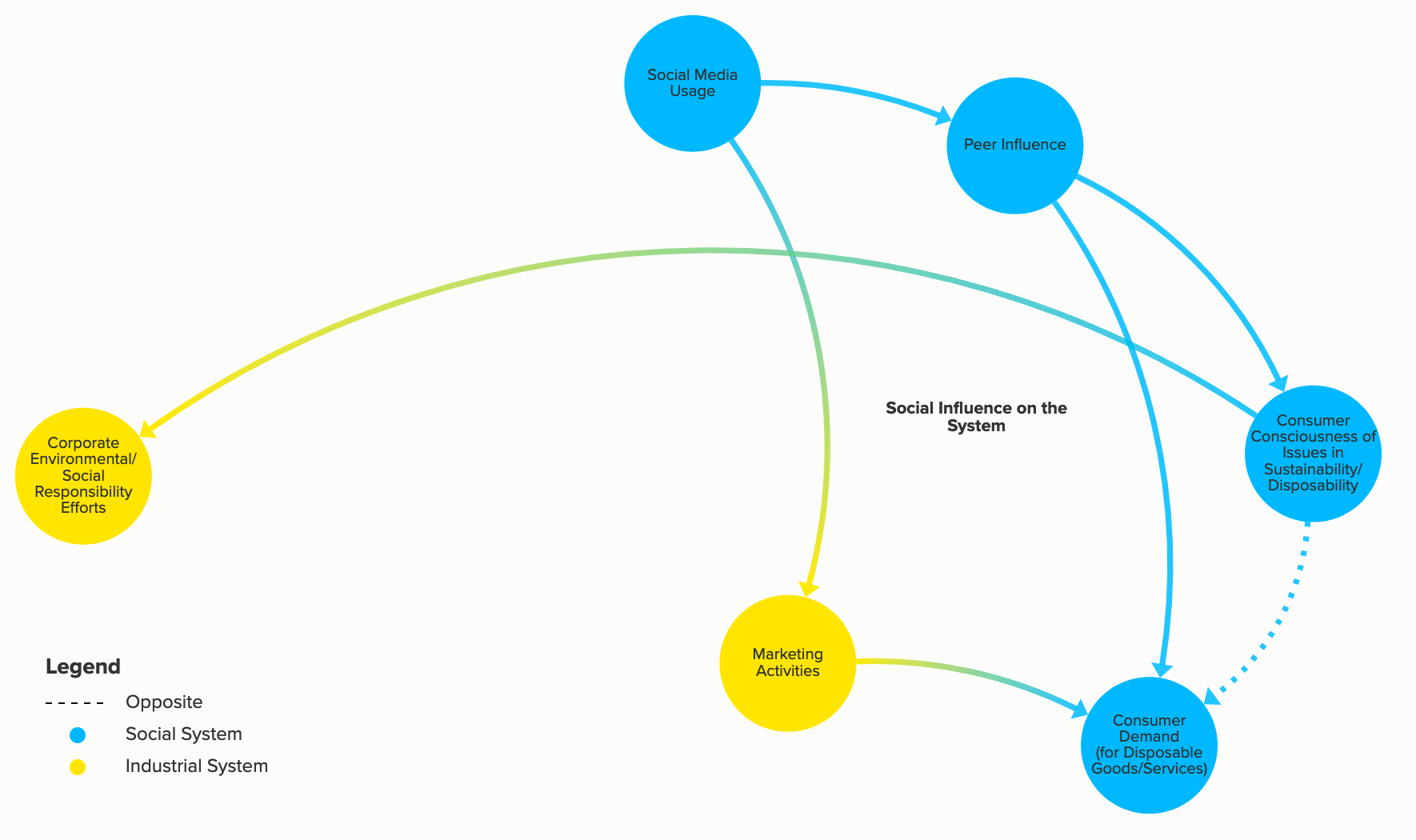

In marketing, this has taken shape through game-changing initiatives like Chipotle’s 2012 “Back to the Start” campaign for sustainable agriculture (Olson, 2012), and Patagonia’s 2011 “Don’t Buy This Jacket” campaign against fast fashion (Patagonia, 2011). The simultaneous emergence of social media represented a paradigm shift for the discipline of marketing, as the impact of those integrity-based campaigns resonated so deeply with the general public that a new bar was set—the “viral” ad. Social media adoption increases peer influence, which, depending, leads to consumption patterns of either the sustainable (e.g., through ocean plastics awareness) or the unsustainable (e.g., “unboxing” and “haul” YouTube videos that glorify the consumption experience) sort. Likewise, the power of the masses online also places incredible pressure on businesses to act in responsible ways, for fear of boycotts and public relations nightmares. Systems can only change if there is widespread recognition that the current version is failing (Gilbert, 2019) and social media has been a platform that opens up information flows, making systems change possible.

Figure 4: Social media’s influence on capitalism, marketing, and demand

Figure 4: Social media’s influence on capitalism, marketing, and demand

The movement towards purpose-driven business is gaining momentum. In 2010, Maryland became the first US state to pass “benefit corporation” legislation (currently, 34 states and the District of Columbia have similar legislation), establishing a class of legal corporate entities with explicit, intentional accountability for achieving positive social and environmental impacts in addition to their profit-oriented business objectives (Barnes, 2017). Similarly, “B Corporation” status is a private, third-party sustainability certification available, through the nonprofit B Labs, to all businesses regardless of legal classification (B Lab, n.d.). To a marketer in an increasingly “conscious consumer” society, these legal and third-party statuses, like others such as “Organic” and “Rainforest Alliance Certified,” are valuable assets—it is a real competitive differentiator to be able to say that a product or company meets sustainability criteria without the fear of greenwashing.

Benefit corporations and B Corp certifications came about as efforts to redefine the purpose of business and give the system a goal beyond just making money for its own sake and without regard for negative externalities. Changing the goal of a system is powerful point of leverage. Although the emergence of benefit corporations and B Corps do not change the goal of traditional corporations, they do shine light on the fact that traditional corporations have no legal accountability towards social and environmental justice, adding pressure, through public sentiment, for all businesses to act more responsibly. Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff’s near-motto that “the business of business is to improve the state of the world” takes this paradigm shift to the global stage (Pontefract, 2017), while economist Tim Jackson’s body of academic and policy work recommends a paradigm shift that decouples the concept of prosperity from that of GDP growth. Jackson recognizes that a prosperous society is not just a financially secure one; it is one that emphasizes health and wellbeing, happiness, and access to quality education (Jackson, 2010). When the goal of capitalism shifts, and the parameters for success change, to include stakeholders instead of just shareholders—the feedback loops and information flows will also re-orient towards that goal.

Another point of leverage is through incentives and disincentives, both in terms of policy regulation at the government level as well as in reforms of success metrics at the corporate level. Today’s businesses, and marketers specifically, can and should reconcile the missteps of their predecessors by supporting legislation around truth in advertising and product quality (which will restore the regulatory balancing loops), and having skin in the game through accountability for the information conveyed in their advertising. This accountability will lead to yet another leverage point by ensuring the existence, accuracy, and thoroughness of information flows between companies’ marketing and product design/quality teams, and their environmental and social impacts. Marketers and executives alike should be incentivized toward long-term success measurements rather than short-term, in an effort to reduce the financial pressure for sales (consumption) growth and repair the unsustainable “Race to the Bottom” cycle of ever-increasing quality reductions that are correlated with disposability. Sustainability, we now know, “is not at odds with the goal of maximizing corporate value; on the contrary, it’s essential to achieving that goal” (Barton, 2011).

The best standard for ensuring long-term sustainability is in working toward the idea of “circularity,” or a “circular economy.” The Ellen MacArthur Foundation is a leading change agent working through corporate partnerships to accelerate this paradigm shift towards circular business models that re-calibrate our production and consumption habits. They define a circular economy as one which redefines growth, decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources by keeping products and materials in use, and designing waste and pollution out of the system. It still builds economic capital, but it also values and builds natural and social capital (n.d.).

Conclusion

Capitalism, as the world’s most successful wealth-creating economic system (Gilpin 2018), has been proven to do very well at advancing the human condition. However, since it is also simultaneously destructive and unsustainable, it is essential that the system be substantially reformed, with goals, incentives, and accountability oriented toward long-term value—doing good and prohibiting harm to other people and to our natural environment. These reforms can begin now; in fact, they already have. Government has never defined capitalism, so there isn’t any sense in waiting for a revised set of requirements. Industry, in its free and individualistic spirit, can bravely start to define for itself what sustainable market landscapes might look like. William McDonough, founder of the circular economy “cradle to cradle” concept says optimistically, “We’re seeing hundreds of small examples of [companies] putting their toe in the water … I think we’ll be surprised how quickly it explodes onto the scene” (Peters, 2019).

If Philip Kotler’s claim was true—that capitalism would have failed without marketing—then marketing surely must play a leading role in fixing it. Although they cannot do it alone, marketers are uniquely situated at the nexus of business strategy, production, and consumption, with the capability and responsibility to spark a shift toward sustainable economic transformation. Marketers previously established disposability as a positive feature; they can turn that around by harnessing their creativity and replacing their win-win (business-consumer) mindset with a win-win-win (triple bottom line) mindset. A long-term approach to capitalism will create antifragility—a strong, resilient, equitable system able to deliver sustainable growth (Barton, 2011). The existing “convenience” paradigm can change. It will not be an easy transformation, and it is full of uncertainties, but it is a necessary transformation that will have a priceless impact.

Appendix: Full System Map of Marketing’s Role and Influences in Capitalism

References

- B Lab. (n.d.) About B Corps. Retrieved March 24, 2018, from: https://bcorporation.net/about-b-corps

- Barnes, A. (2017, November 29). Joining Trend, WI Creates New Business Entity: Benefit Corporations. Xconomy. Retrieved from https://xconomy.com/wisconsin/2017/11/29/joining-trend-wi-creates-new-business-entity-benefit-corporations/

- Barton, D. (2011, March). Capitalism for the Long Term. Harvard Business Review (89)(3), 132–132.

- Belz, F., and Peattie, K. (2012). Sustainability Marketing. West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

- Braudel, F. (1979). The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (n.d.). What is a circular economy? Retrieved March 24, 2019 from: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept

- Formafantasma. (2019, February 27). Ore Streams [Video file]. Retrieved from: https://vimeo.com/320151239

- Gilbert, J. C. (2019, January 24). Larry Fink, Tucker Carlson, David Brooks And The Call For A Capitalist Reformation. Forbes. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jaycoengilbert/2019/01/24/larry-fink-tucker-carlson-david-brooks-and-the-call-for-a-capitalist-reformation

- Gilpin, R. (2018) The Challenge of Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Greenspan, A., and Wooldridge, A. (2018). Capitalism in America: A History. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Jackson, T. (2010, July). An economic reality check [Video file]. Retrieved from: https://www.ted.com/talks/tim_jackson_s_economic_reality_check

- Kornbluth, J., and Gilman, S. (Directors). (2017, November 21). Saving Capitalism [Motion picture]. USA: Netflix.

- Kotler, P. (2016, August 25). The Relationship between Marketing and Capitalism. The Marketing Journal. Retrieved from: http://www.marketingjournal.org/the-relationship-between-marketing-and-capitalism-phil-kotler/

- MacFarland, S. (2014, May 23). 7 Reasons Why I Am a #Marketing Junkie. Huffington Post. Retrieved from: [https://www.huffingtonpost.com/scott-macfarland/7-reasons-why-i-am-market_b_5375230.html] (https://www.huffingtonpost.com/scott-macfarland/7-reasons-why-i-am-market_b_5375230.html

- Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Olson, E. (2012, February 9). An Animated Ad With a Plot Line and a Moral. The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/10/business/media/chipotle-ad-promotes-sustainable-farming.html

- Patagonia. (2011, November 25). Don’t Buy This Jacket, Black Friday and the New York Times. [Web log post]. Retrieved from: https://www.patagonia.com/blog/2011/11/dont-buy-this-jacket-black-friday-and-the-new-york-times/

- Peters, A. (2019, February 5). Most U.S. companies say they are planning to transition to a circular economy. Fast Company. Retrieved from: https://www.fastcompany.com/90300741/most-u-s-companies-say-they-are-planning-to-transition-to-a-circular-economy

- Pontefract, D. (2017, January 7). Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff Says The Business Of Business Is Improving The State Of The World. Forbes. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/danpontefract/2017/01/07/salesforce-ceo-marc-benioff-says-the-business-of-business-is-improving-the-state-of-the-world

- Rudawska, E. (2017, April 17). Sustainable Marketing Concept – A New Face of Capitalism. British Journal of Research, (4)(2).

- Tantram, J. (2014, May 19). What’s the Point of Capitalism? Sustainable Brands. Retrieved from: https://sustainablebrands.com/read/defining-the-next-economy/what-s-the-point-of-capitalism

- United Nations. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. [Report]. Retrieved from: http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf

Stay In Touch!

Get occasional letters from Michael & Hannah.